Final Fantasy XVI: Dissonance & Disappointment

July 21, 2023

- SPOILER WARNING: A lot of spoilers in this one -

About 25 years ago, at a mall somewhere in Virginia, I got my first Final Fantasy game. It was Final Fantasy VI – marketed as Final Fantasy 3 at the time on Super Nintendo – and I convinced my mom to buy it for me from the bargain bin outside some presumably now-defunct toy store. In that pre-internet era, I’m not sure how I even knew about it, but I did. It was a game I had been looking for. Even then, Final Fantasy was calling to me.

Since then, I’ve played every mainline Final Fantasy game (with the exception of number five, I’m getting there, it’s not my fault), some of them many times. I’ve spent somewhat regrettable time with offshoots, like Mystic Quest, and logged an absolutely disgusting amount of time into decorating my apartment and dominating the fantasy gig economy in Final Fantasy XIV. There have been few periods in my life where there hasn’t been some kind of Final Fantasy nearby, desperately trying to satiate my desire for more absurd, crystal-based adventure.

The thesis statement of all Final Fantasy games.

Final Fantasy XVI should have been perfect for me, then. Even the big variation it brought to the Final Fantasy formula – a darker, grittier, Game of Thrones-style setting – didn’t raise any red flags. Anybody who’s played The Salt Keep knows that there are few things I love more than mud-soaked medieval peasants having a bad time near a traditional European castle. Still, I found myself faltering very quickly, increasingly frustrated as the game missed me as a target again and again. It wasn’t any one thing, either, but the complete experience.

The game wants to be a lot of different things. Sometimes it’s a grim narrative grounded in harsh reality, while other times it’s a bombastic anime romp full of half-baked mechanics. While there’s no reason a game can’t have wild tonal shifts – I love the Yakuza series, after all – it takes a certain finesse to hold them together, and I’m not sure that Final Fantasy XVI has it. From start to finish, my experience with the game was marked by a sense of dissonance.

THE NARRATIVE

For me, the problem started with the narrative, and it was almost immediate. The first clue was one of the opening cinematics, which depicted a front-line battle between two military forces, neither of which I knew at the time, and neither of which, even in retrospect, I can confidently name. Blood splattered as soldiers clashed with each other – we’re doing gritty Final Fantasy this time, the game seemed to say – and my nostalgia-addled synapses fired as the cavalry charged in, warriors mounted on chocobos instead of horses. There was a tonal mismatch between the inherent goofiness of chocobos and the muddy slaughter portrayed, but at that point, I was open to it. What a fun and absurd juxtaposition, I thought.

That juxtaposition persisted, though, and became increasingly unwelcome as the story continued into weightier territory. The early plot is completely focused on the plight of the bearers – magic-users whose oppression serves as a ham-fisted slavery metaphor – and the relationship that the protagonist, Clive, has with them. Despite having been pulled from a privileged position as the personal bodyguard to his nerd brother and cast into slavery himself, Clive seems continuously surprised and confused by the realities of the practice. He acts as an audience proxy, grunting in his best impression of Henry Cavill doing his best impression of Doug Cockle every time he witnesses some new horror. “But that’s wrong,” he says as the game leads you through quest after quest of comically evil masters subjecting their bearers to grotesque torture, as if trying to persuade the audience that slavery is, in fact, bad.

I wonder if anybody has ever crucified a moogle.

A ham-fisted metaphor isn’t a bad thing in and of itself, but the game makes no real effort to grapple with its weighty subject matter. It doesn’t have anything meaningful to say about it, and seems to view the social and political hierarchy that led to such brutal injustice as little more than the arbitrary bigotry of individuals. It suggests that it’s a problem that can be solved by, for example, some gold-hearted little kids running into a town square and saying, “wait, everybody, this particular bearer is actually really cool and helpful, don’t murder him in cold blood like you were about to!” That’s enough, in the world of Final Fantasy XVI, to change hearts and minds.

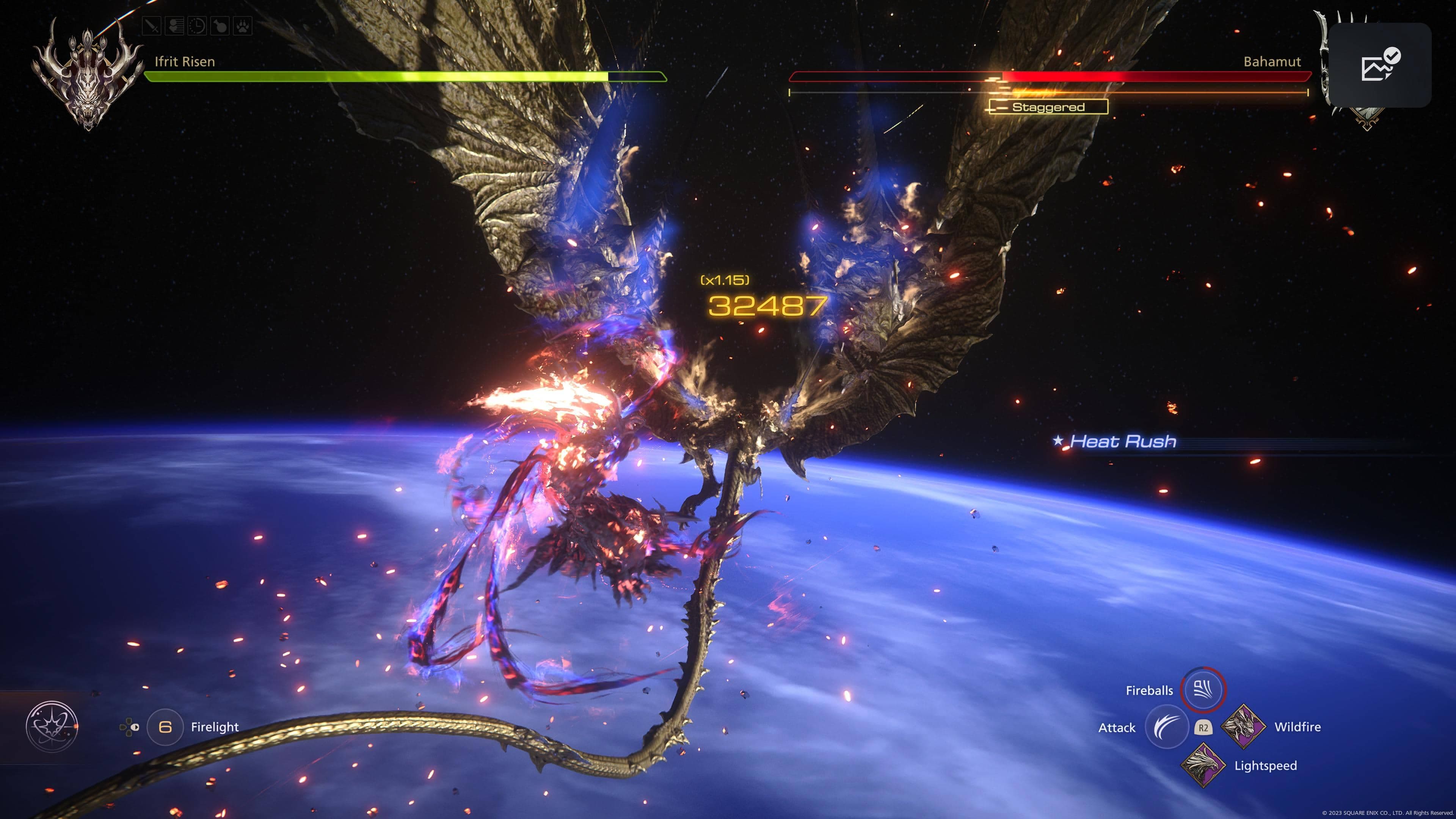

Rather than grapple with the topics the story has introduced, it seems that what the game really wants to do is Final Fantasy stuff. Between these bleak and grounded depictions of political turmoil and banal evil leading to what amounts to genocide, the game launches into over-the-top anime-style spectacle battles, where giant demon mecha mash each other through consequenceless quick-time events at such a blistering pace and meteoric scale that your screen becomes a blur of color-coded sparks and flames. Locations become abstract and gravity seems to loosen as all action takes to the air, and giants punch each other between “powering up” noises. I never thought I’d see Ifrit say “fuck,” but now I have.

Every scene in the game is either a mud puddle or this.

Again and again, we have this spectacle. The scale of Clive’s struggle seems to grow exponentially, leading to bizarre pacing that has the story feeling like a climax is imminent at all times. Everybody loves to point out how JRPGs are all about killing God, and this one is no different – the final chapters are full of droning, philosophical monologues from straight-up God, a blank-eyed weirdo just begging to be killed – but it feels like Clive is killing gods from the start. As early as Benedikta, he already reads as a tremendous, unstoppable power, murdering gigantic cosmic beings and absorbing their power like some kind of gruff and sexy anime Kirby.

Immediately after a battle of such epic scale, however, the game will drop you right back into your gritty routine, running errands for various surly shopkeepers at your hideaway or collecting leaves for some idiot who wants to grow fruit in the wasteland, then wandering around a grounded landscape of political intrigue and mundane human suffering. Tonal whiplash is something I could probably forgive on its own, but it all seems to stem from that same central problem: the game wants to be both of these things at once – grounded gritty realism and soaring anime flamboyancy – but it makes little effort to combine them.

THE GAMEPLAY

The problem with the juxtaposition becomes even clearer in the gameplay. Don’t get me wrong: the combat is fun. You feel that sweet Devil May Cry DNA every time Clive goes flying, slashing his improbably-crafted sword in mid-air, and the regular addition of new abilities keeps you experimenting and leaning into new combos. Your various skills work together in a way that just generally feels good, flowing intuitively so that whatever you think should be happening when you try to string some buttons together is pretty much what ends up happening.

At first, everything chugged along just fine, the combat flowed, and I didn’t think much about it, but as with the narrative, a gap began to widen as the game progressed. The actual action of combat remained similarly satisfying throughout the game, but the RPG side of things – the gear I equipped, the experience I earned to level up, the party members who sometimes accompanied me – seemed to get lost. Rather than understanding the mechanics more throughout the game, I almost felt the opposite. It wasn’t clear to me whether changes to my stats made through gear or levels really did much of anything, and I rarely paid any attention to whether there were party members joining me or not. None of it seemed to particularly matter.

Nowhere was that clearer to me than in the many color-coded damage numbers that flashed on the screen during combat. Every attack you make throws out a number, and the sheer quantity of them seems to demand that you pay attention, but I never felt like I could really learn much from them. I didn’t have a sense that they were growing significantly as I leveled up or equipped new gear, and as a result, I was never quite clear what they were trying to tell me. They felt almost like an aesthetic signifier – this is an RPG, so here are some numbers – without any meaningful connection to the actual gameplay. Two disparate ideas, barely related.

32487 damage, that must be a lot, or perhaps barely any.

The gap continued widening with the design of some of the structural elements of the game. Clive is informed early on, for example, that he can find new quests using the Alliant Reports desk, where one of his many sparsely-developed hideaway buddies is waiting to dole out missions for him to complete. When I first heard that, my eyes lit up with excitement – that’s Video Game stuff, I thought, I love doing Video Game stuff – but when I then went to the Alliant Reports desk to take on some missions, I found that there weren’t any. That trend continued almost every time I checked in on my Alliant Reports: nothing to see here.

Eventually it became clear that it wasn’t a place that handed out missions, so much as a place that pointed out filler missions that already existed somewhere in the world. If you found those missions organically and completed them, then, there’d be none to see at the desk. As a quality of life mechanic, it wasn’t a bad thing necessarily, but unsatisfying. It felt like a structure plucked from an MMO and grafted onto a single player narrative experience, as if somebody imagined the Daily Tasks you might find to encourage the player to log in every day, built the structure for it, then realized that a single player game with a finite narrative doesn’t have Daily Tasks.

We are on a quest to solve slavery by scolding bigoted peasants.

Other elements felt similarly out of place, like the equipment and crafting systems. On one level, equipment felt like it functioned almost as it would in an old-school JRPG – at various points in the story, shopkeepers just had new, better items, and I bought them – but the crafting system seemed to want to add some complexity. Rather than offering any real decisions to make or even reasons to hunt any particular monsters, the crafting just required a handful of materials that I invariably already had and didn’t even remember getting, and conferred a bonus that I couldn’t recognize as meaningful in combat. Like the Alliant Records, it felt half-baked, like an idea from a different game that was grafted onto this one not because it adds much of anything, but just because that’s the kind of thing RPGs usually do.

THE INTERSECTION OF THE TWO

For me, the most frustrating example of this tonal disconnect is in the activity that most clearly combines gameplay and narrative and fills the bulk of your time playing: the sidequests. A few of them are exactly what I’d hope to see in this kind of game – the wrap-up quests that the major side characters offer just before the final mission, for example, like Torgal guiding Clive to the island where they find his childhood fort – but far too many read as “filler” more than anything else. It’s a huge game, so it shouldn’t surprise anybody that there’s going to be some variation in quality and narrative significance, but a significant number of the sidequests feel almost intentionally neutral. It’s not that they’re bad, necessarily, but that they’re nothing.

The game is absolutely crawling with named side characters, for example, most of whom are barely explored in any meaningful way. Instead, Clive spends huge amounts of time doing fetch quests for local nobodies we meet once and never again. If they contributed in some substantial way to worldbuilding, even that would feel okay, but they often felt more like absurdly superficial morality tales. One with an innkeeper in Dhalmekia sending me out to gather three other locals to share wine with him stuck in my mind as a succinct illustration of the problem, as none of the four were characters I knew, and the significance of their meeting seemed to amount to an eye-rollingly pointless “it takes all kinds to run a marketplace” moral.

Ah yes, the three pillars of Boklad, the ones we know and love.

The problem circled back to that narrative flaw in which the game seems to want to discuss weighty issues without actually discussing them. It felt like any number of the filler sidequests may have been intended as meaningful worldbuilding, but I was constantly grasping for anything more than yet another superficial reminder that the world is bad and has bad people in it. Clive never seemed to have his worldview challenged, or even define his worldview outside of some general “good guy” defaults, and most of the other major characters were the same. I was constantly struck by how much time we spent with Jill, for example, and how little I knew about her by the end of the game. She was just there, barely defined, with nothing in particular to say.

As a result, most of the sidequests felt less like satisfying narrative detours, and more like that equipment crafting system: a feature that exists not because it’s doing anything for this game in particular, but because it’s the kind of thing this sort of game usually has. Each of the tonal extremes felt similar in that sense, like an exercise in familiar aesthetics. We’re doing gritty grimdark, so let’s have hanging bodies and people wailing, but we’re also doing anime romp, so let’s make sure everybody’s improbably hot. We’re doing Devil May Cry action, so let’s put a bunch of cool movesets in there, but we’re also doing RPG, so let’s add a bunch of random numbers. A decades-spanning saga on one hand, checklist filler quests on the other.

Is this a better world? Is this what Clive even wants? I don't know.

A lot of these grievances exist just as much, if not more, in other JRPGs I’ve played and enjoyed without complaint. Blank slate protagonists are a staple of the genre, after all, and there’s no shortage of bad politics, simplistic worldviews, and superficially-defined characters to be found. Similarly, weighty human trauma is a fairly common video game theme these days, and even if I can’t think of another ham-fisted slavery metaphor off the top of my head, I’m sure it exists. None of the things I’m complaining about here are unique to Final Fantasy XVI.

What does feel unique, however, is that the game wants to do all of them at once. It wants to show me the depths of human cruelty as Clive stares up at a spread of semi-crucified bodies, an image pulled straight from the pages of Berserk. Then it wants to direct me to the Hunt Board where I track down an arbitrary series of ranked monsters to check them off the list, a mechanic pulled straight from an MMO. I veer wildly between these two tonal extremes, open to either of them, open to both, but neither fully commits to what it wants to do, seemingly out of fear of undercutting the other. Both are half-realized, yet they expect me to be immersed.

At least I got to kill god, though.

If you like this kind of thing and want to see more of it, or if you want to support the development of any current or upcoming games, please consider subscribing on Patreon.